Inviting someone into your class to observe you teach gives you the chance to receive feedback from an objective source. Teaching observations can be a source of specific information about your teaching effectiveness. They can also provide you with insight into areas for growth, and can serve as a way to help you respond to specific challenges you are facing in your class.

Inviting someone into your class to observe you teach gives you the chance to receive feedback from an objective source. Teaching observations can be a source of specific information about your teaching effectiveness. They can also provide you with insight into areas for growth, and can serve as a way to help you respond to specific challenges you are facing in your class.

Click on the links below for more guidance on best practices for observing and being observed by your peers. See the sidebar for tools you or your observer might use to complete the process.

Want some help? Contact us via ctlhelp@gatech.edu!

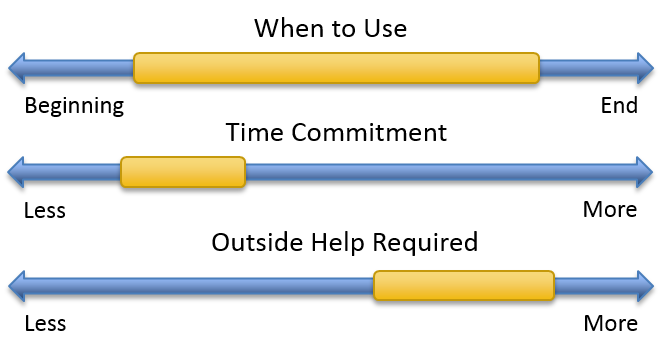

Teaching observations are useful at any time during the semester, but unless there are special circumstances, it is useful to wait for at least the third week of the semester. This is so that your students' behavior and experiences will have settled into a routine, and the data collected will be more representative of the experience in your classroom. It is also useful to schedule your observation early enough in the semester to allow you to implement responses to the feedback you receive, thereby impacting your current students' experience in the class. Finally, it is advisable to schedule your teaching observation around anything that might upset the normal trajectory of your course (e.g., week before or after a major test).

Collapse this section

When finding someone to observe you teach, look for someone you trust to give you honest and constructive feedback about your teaching. Beyond that, consider the following three factors:

- Discipline: It can be useful to have someone from outside your discipline observe you teach: they are often better able to focus on your teaching strategies, without focusing on your selection and interpretation of content. On the other hand, colleagues in your field can provide feedback from the perspective of someone who has taught similar content.

- Experience: It can be useful to get feedback from a senior colleague, or someone who has had more time to develop their approach to teaching. On the other hand, peers can be a nonthreatening source for feedback on teaching, and a free exchange of ideas can occur when you take turns observing each other teach.

- Teaching Expertise: Teaching award winners, pedagogy experts from the Center for Teaching and Learning, and others who have developed a broad knowledge base about research in teaching and learning can be an excellent resource for feedback on your teaching.

Collapse this section

(See the sidebar for additional tools to help you and your observer engage in an effective observation experience.)

- Share information with your observer, before your class, about your course and your motivations for the observation.

- Teach your class, with the observer present (ideally sitting unobtrusively in the back of the classroom).

- Reflect on the class (before you meet with your observer). As instructor, take some time to identify what went well/as expected during your class. The observer should take time to reflect on their observations, and prioritize feedback with respect to both strengths they have observed, and suggestions they have for you.

- Discuss your experience and your colleague's observations.

- Respond to your colleague's feedback by creating an action plan for specific adjustments to your teaching.

Collapse this section

Providing feedback on teaching is much like providing feedback to students: it is most useful when it is delivered with respect, specificity, and a combination of explanation, identification of strengths, and suggestions for improvement. Adapted from Berquist and Phillips (1975), the following list will help you frame your feedback for positive impact. Constructive feedback is:

- Actionable

Frustration is only increased when a person is reminded of some shortcoming over which she/he has no control. Instead, give feedback focused on changes the individual can make.

- Based on observable behavior

Telling people what their motivations or intentions are can contribute to a climate of resentment, suspicion, and distrust. Feedback that contributes to learning and development is focused on the behavior that has been observed.

- Communicated clearly

No matter what the intent, receiving feedback can often feel threatening. As a result, feedback can undergo considerable distortion or misinterpretation upon receipt. Aim for straightforward and clear communication to minimize this effect.

- Descriptive

Evaluative language can leave the recipient feeling judged and defensive, and thereby less likely to respond positively to feedback. Provide descriptions, but avoid evaluative language that judges perceived quality of teaching.

- Focused on behavior

When feedback is articulated as a personality trait, it implies that the feature is fixed. When it is focused on behavior, it allows for the possibility of change.

- Followed by discussion of next steps

Discussing next steps together increases the likelihood that the recipient of feedback will implement positive change to increase their effectiveness.

- Formulated to serve the needs of the recipient

Feedback can be destructive when it serves only our own needs and fails to consider the needs of the person on the receiving end.

- Manageable

To overload a person with feedback is to reduce the possibility they will be able to use the feedback effectively. Instead, prioritize feedback and highlight only a few main points.

- Presented as information

By sharing information, we leave people free to decide for themselves, in accordance with their own goals and needs.

- Solicited

Feedback is most useful when the receiver actively seeks feedback.

- Specific

General claims or comments are difficult to grasp (e.g., “you dominated the discussion”); specific examples lend credibility to the feedback.

- Timely

In general, feedback is most useful at the earliest opportunity after the given behavior.

Collapse this section

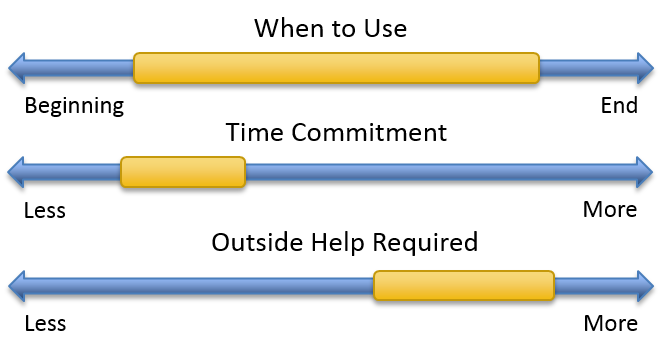

COPUS is an easy-to-use observation protocol developed specifically for capturing data about how class time is used, with a focus on the incorporation of opportunities for active learning. The observer tracks classroom activities in two minute intervals, and uses that data to create a profile of the class that has been observed. This profile provides a starting point for reflection and discussion about your use of class time, and allows you to consider different ways to incorporate active learning into your teaching.

For more information about COPUS, and for tools to implement the COPUS profile in your classroom, visit the following resources:

Collapse this section

- Berquist, William H. and Phillips, Steven R. (1975). A Handbook for Faculty Development, Volume 1. Dansville, NY: The Council for the Advancement of Small Colleges.

- Brinko, Kathleen T. (1993). The Practice of Giving Feedback to Improve Teaching. Journal of Higher Education. 64(5): 574-593.

- Nyquist, Jody D. and Wulff, Donald H. (2001). Consultation Using a Research Perspective. Chapter 3 (pp. 45-62) in Face to Face: A Sourcebook of Individual Consultation Techniques for Faculty/Instructional Developers. Edited by Karron G. Lewis and Joyce T. Povlacs Lunde. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press, Inc.

- Smith, Michelle, Francis Jones, Sarah Gilbert, and Carl Wieman (2013). The Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM (COPUS): a New Instrument to Characterize University STEM Classroom Practices. CBE-Life Sciences Education. 12(4): 618-627.

- Theall, Michael and Franklin, Jennifer L. (2010). Assessing Teaching Practices and Effectiveness for Formative Purposes. Chapter 10 (pp. 151-168) in A Guide to Faculty Development, edited by Kay J. Gillespie, Douglas L. Robertson, and Associates. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Collapse this section

Inviting someone into your class to observe you teach gives you the chance to receive feedback from an objective source. Teaching observations can be a source of specific information about your teaching effectiveness. They can also provide you with insight into areas for growth, and can serve as a way to help you respond to specific challenges you are facing in your class.

Inviting someone into your class to observe you teach gives you the chance to receive feedback from an objective source. Teaching observations can be a source of specific information about your teaching effectiveness. They can also provide you with insight into areas for growth, and can serve as a way to help you respond to specific challenges you are facing in your class.